.png&h=570&w=855&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

The Chinese social-media app Red (known as Xiaohongshu or Little Red Book in China or RedNote in its international version) has been in the spotlight since last weekend. Approximately 500,000 users, who tend to refer to themselves as ‘TikTok refugees,’ have migrated to the app to continue sharing content and connecting with others, making RedNote the top social-media platform among all free apps in Apple’s App Store last week.

The recent surge in American users has sparked fascinating cultural exchanges on the platform. One notable example is the way US users have begun responding to ‘Li Hua’, a name frequently featured in Chinese middle school English exams.

Stocks of companies related to Red in China, or concept stocks of Red, also experienced significant growth in their market caps last week due to the sudden influx of international traffic to Red.

As of January 19, Red officially launched a translation feature that allows users to communicate with each other. According to a test by Chinese media outlet Fast Tech, the translation feature supports various languages, including French, Japanese, and Lao. Additionally, trendy Chinese internet slang expressions such as ‘YYDS’ (similar to ‘GOAT’ in English), ‘U1S1’ (to be frank or honest), ‘U Can Up’ (If you think you can do it better, then do it.), and ‘XSWL’ (laughing myself to death) are also included in the translation feature.

On the same day, TikTok temporarily shut down in the US but restored services later that day after President-elect Donald Trump promised to issue an executive order to bring the app back online. Even before the US Supreme Court upheld a federal law requiring TikTok to be sold by its China-based parent company, ByteDance, or face a shutdown, American users began downloading RedNote, referring to themselves as ‘TikTok refugees.’

Last week, Red reportedly began hiring English content reviewers. Campaign reached out to Red, but they did not comment at time of publish. Red established its Hong Kong team late last year, and the initiative was viewed as a significant step toward expanding into international markets.

In light of the recent surge in popularity of RedNote and Little Red Book, Campaign asked marketing experts from both China and international markets to assess the potential risks and challenges that RedNote may face, whether it should reconsider its international expansion strategy and what lessons brands and platforms could learn from the series of incidents.

A double-edged sword for Red?

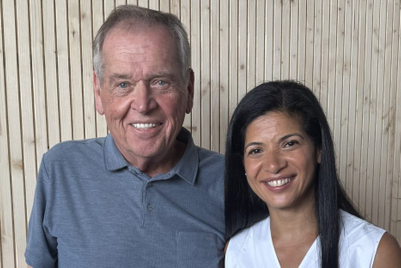

Nicky Wang, the CEO of WE Red Bridge, recognises that the growing number of American users on Red presents both opportunities and challenges. She describes the sudden international exposure as a “double-edged sword”.

Wang expresses concern that the integration of TikTok-style content with Red's focus on lifestyle could disrupt the platform's carefully curated ecosystem, impacting the user experience. Despite the app's swift translation functions, she worries that cross-cultural misunderstandings pose a considerable risk.

Furthermore, Wang highlights regulatory concerns from both the US and China. She notes that American users' vocal frustrations with the US government on Red could lead to increased scrutiny from Chinese regulators.

Wang added: "Red's lack of creator monetisation features may hinder the long-term retention of international influencers."

Chris Baker, founder of Totem, a brand strategy and social digital agency, agrees that this situation has both high rewards and risks. He described Red as “China’s best-kept secret social-media app," Although its current scale is relatively small, it may not pose an immediate threat.

He added: “It could become a blinking light for US lawmakers if the trend continues. Chinese regulators might also be very nervous about having millions of Americans freely interacting with Chinese users on Red”.

In the short term, he anticipates some potential issues with “a rush of international users on Red creating disruptions for the foundational Chinese users, such as a misinterpretation of a comment or post, or skewing of algorithms away from core Chinese users”.

Bryce Whitwam, co-host of the ShanghaiZhan podcast, raises the question of whether this could be a pivotal moment for Rednote on WeChat. He recalls that in 2012, WeChat experienced explosive growth in China, partly due to a crackdown on Weibo's ‘big VIP’ accounts—mega-influencers with millions of followers. Users seeking a more private alternative flocked to WeChat, leading to a surge in adoption that forever transformed China's social media landscape. As a consequence, he said that Weibo has never fully recovered its former dominance.

He also spoke of the challenges faced by users in the US with Rednote: “First, Rednote and TikTok serve different purposes, so American users will need time to understand how Rednote fits into their existing social media ecosystem. Additionally, Rednote must navigate the complex regulatory environment that has posed challenges for LinkedIn in its attempts to operate globally, especially regarding China's Great Firewall. Some American users have already experienced account removals due to content violations, and this may be just the beginning of moderation challenges for Rednote”.

Ali Zein Kazmi, co-host of the ShanghaiZhan Podcast and principal consultant of Serpons, also discussed the potential threats for Red including “scaling internationally while adapting to diverse cultural expectations, maintaining trust through robust privacy protections, and navigating heightened geopolitical tensions”. He concluded that these factors will “determine whether Xiaohongshu can sustain its appeal and capitalise on this pivotal moment of user migration” in the near future.

What’s next for Red’s international strategy?

Both Baker and Whitwam agree that Red will eventually need to create two separate versions of the app, potentially renaming the global version. Ultimately, the platform must distinguish between the two apps to ensure that Chinese users do not see Western content and vice versa.

Kazmi believes that the platform's vibrant community will foster authentic engagement, while the cultural fluidity of its users provides a unique advantage in reaching diverse audiences.

He said that to succeed internationally, Xiaohongshu must carefully balance localisation with the preservation of its “tight-knit, culturally rich community”. However, achieving this while addressing concerns around transparency, privacy, brand safety, and inclusivity will be critical to sustaining trust and scaling in non-Mandarin markets.

Wang emphasised the importance of investing in robust and multilingual content moderation to preserve Red's authentic user experience. She also believes that creating a sustainable global business model which utilises cross-cultural marketing opportunities and engages overseas KOLs, is essential for long-term success. Additionally, she highlighted the need to enhance security measures to address potential concerns from international users and regulators.

Baker noted that where Chinese marketing is mostly organised around social commerce, in the US, legacy players (such as Meta) are trying to maintain a more static ad model.

Whitwam described himself as an optimist, noting that while American users make up 12% of TikTok’s global active user base, Rednote has managed to achieve the top position on the app charts. However, it has attracted only around 500,000 of the 122 million active TikTok users in the US. This suggests that Rednote may not be adequately prepared to compete for the attention of American users, he said.

Meanwhile, Kazmi believed that despite legislative efforts and regional restrictions, the creator economy continues to transcend borders. This phenomenon, which is referred to as "app fluidity," is still in its early stages. Users now navigate multiple identities and modes of engagement—whether conformist or non-conformist, passive or active, attention-seeking or entertaining—across diverse platforms and devices.

He added that this adaptability marks a new era of digital behaviour, where individuals operate in ways that redefine identity, culture, and the boundaries of entertainment.

Lessons to consider

Wang emphasised the importance of digital agility as a key takeaway, noting that the Red phenomenon underscores the need for brands to be nimble in their digital strategies, allowing them to quickly respond to unexpected platform shifts and rapidly changing user behaviours.

She referred to the Red migration as “a rare moment of direct cultural exchange between US and Chinese citizens on a large scale, fostering unexpected connections during a time of increasing geopolitical tensions.”

"This phenomenon challenges the notion that US-China decoupling in the digital sphere is inevitable, demonstrating that users are willing to bridge divides when given the opportunity. Additionally, she noted that Red’s rapid response to this influx sets a new standard for platform adaptability in the face of sudden changes to the user base,” she said.

Arielle Garcia, the chief operating officer of Check Ads Institute, stressed the need to listen to your audience. She said: “Some joined [Red] in search of a comparable platform. Many joined in rebellion against the ban, with some users feeling compelled to push back against feeling ‘forced’ into moving to Meta, in light of its recent policy changes and self-serving lobbying against TikTok”.

Ultimately, she believes that brands shouldn’t default to abruptly shifting and concentrating all of their investment into Meta, YouTube, or other dominant platforms.

She said: “Now is the time to diversify investment within and beyond social, and not to assume that users or creators will resign themselves to the status quo of the platforms that they feel have undermined their autonomy or deprioritised their experience”.

.jpg&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=268&w=401&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)