After all, TV is the very definition of mass media. But the schism has become an issue to the industry, in a way that should concern advertisers.

The irony, in the words of Astro’s COO Henry Tan during the closing session at Cassbaa convention in Hong Kong, is improving service to subscribers only earns ire from advertises.

The catch, as he explained it is “TV is becoming increasingly complicated but advertisers want a simple, short solution. The reality is there isn’t a simple, short solution if you want a good, effective one.” And therein lies a conflict.

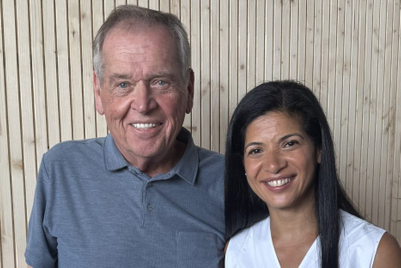

At the conference, TV executives from around the world come together for a few days to discuss industry challenges and possible solutions. Piracy is an unrelenting anxiety that may never be exorcised from these events but in the closing talk on Wednesday, two APAC TV giants, Tan and Ricky Ow, APAC president of Turner, spoke frankly about the ancillary challenges that branch off from the issue.

As with the print industry, advertisers fund a great deal of TV’s operations and profit. So operators, channels, studios and networks all need to protect their turf in order to keep the mass audiences that attract those advertisers. Piracy of course threatens that but as it turns out so do some of the piracy solutions.

From the convention overall, it’s clear the TV industry recognises that there is demand for the medium’s content to be available on other screens, in non-linear fashion and compatible with other formats. Even Tan himself agreed, as a consumer, he wants what he wants when he wants it. And more than once speakers and audience members suggested it might be time to adopt an iTunes-like approach, giving people an easy to use a la carte way to pay for content.

Behind what you watch on the big screen is a huge ecosystem. One set of players owns the delivery (cable, satellite, free-to-air), another the channel or network brand and still another owns the studios and content production. It's a system that’s evolved since the medium’s birth and like a giant steamship, it is not about to change course in the span of a few years. If a studio, for example, was to make its content available easily and directly to consumers, it could find itself locked out of the rest of the food chain and the risk of starvation in that case is real.

At the same time, pay TV subscriptions are still growing organically. Despite the digital pressures of piracy and cord cutting, businesses that own the TV pipes feeding content into homes are still seeing their markets expand, especially in APAC where emerging markets are the tide lifting all boats. So in short, there is still too much money to be made via the tried-and-true model to yet warrant any change.

Abandoning the old way for something new, at this stage, is not a likely decision any of the players are willing to make. These are mainly large firms, many multinational, and all run by boards, shareholders, committees,etc. To shift direction they would all need alignment but consensus decisions rarely take you anywhere other than a place of guaranteed income. No one loses a job where money still being made, even if the market has an entirely different prospect plainly visible on the horizon.

In the US in the 1970s, the country’s auto makers kept churning out big cars, unconcerned with fuel costs and believing Americans didn’t care what a new model was like so long as it was bigger than last year’s. What followed was a mass surrender of market share to foreign brands making smaller cars (ie what the public wanted). There might be a lesson in there.

The TV viewing public has made it clear they still want TV content but they want to consume it differently.

“You talk about TV everywhere—it complicates the way you aggregate and measure the performance,” Tan highlighted. Because of that complexity, he speculates, advertisers then tend to delegate the responsibility of unwinding the issue to their procurement departments. But the mindset at that juncture also has its own bias, one that will be familiar to readers looking at the industry from an ad agency perspective. Tan says the base line for procurement is, “How many people [viewers] do you get and what’s the lowest price?”

“Now seriously, is that how you measure quality?” he asked. “The practice,” he said, is still focusing on “as many as possible, as cheap as possible.” Astro is the largest pay TV platform in Malaysia and Tan contends that the company’s responsibility is to give its paying customers engaging content, when, where and how they want it. That’s his point on quality. “But that’s not even factored in, in terms of advertising value,” he said.

“The more I serve my customers [offering content on mobiles or with time shifting, HD, etc], the more I’m penalised from advertising,” Tan said. Each innovation, HD, multiscreen viewing and IPTV, which his customers demand, fall outside the traditional metrics that advertisers rely on to gauge their TV spending. So in short, immeasurable essentially means non-existent.

Both Ow and Tan agreed that measurement methods have not caught up to viewer habits. But there is substantial time and tradition invested in the existing system and, more concretely, changing it means major monetary investment.

Print has faced almost the exact same set of circumstances and resistance to change ultimately trounced newspaper profits. Again it’s worthwhile to bring up the chart that shows ad revenue plummeting back to 1950 levels.

Programmatic buying on digital platforms has shown that advertisers like to buy specific sets of eyeballs that are well engaged with the content they are consuming. Print publishers had a great deal of trouble accepting digital metrics early on but those who have learned to utilise it, such as Buzzfeed and Huffington post, are demonstrating profitability.

Old measurement methods count the quantity of views [or readers]. But digital measurements can be a better meter for quality. And the later is the metric Tan and Ow advocated during the closing session at Casbaa. But it seems everybody in the industry is still looking to the next guy to go first.

“So what’s holding us back?” session host and PwC’s global lead for entertainment and media, Marcel Fenez asked.

“Ask him,” said Ow pointing at Tan.

.jpg&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=268&w=401&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)